This webpage was created by Joe Schmutz on 3 May 2023 and last updated on 21 May 2025.

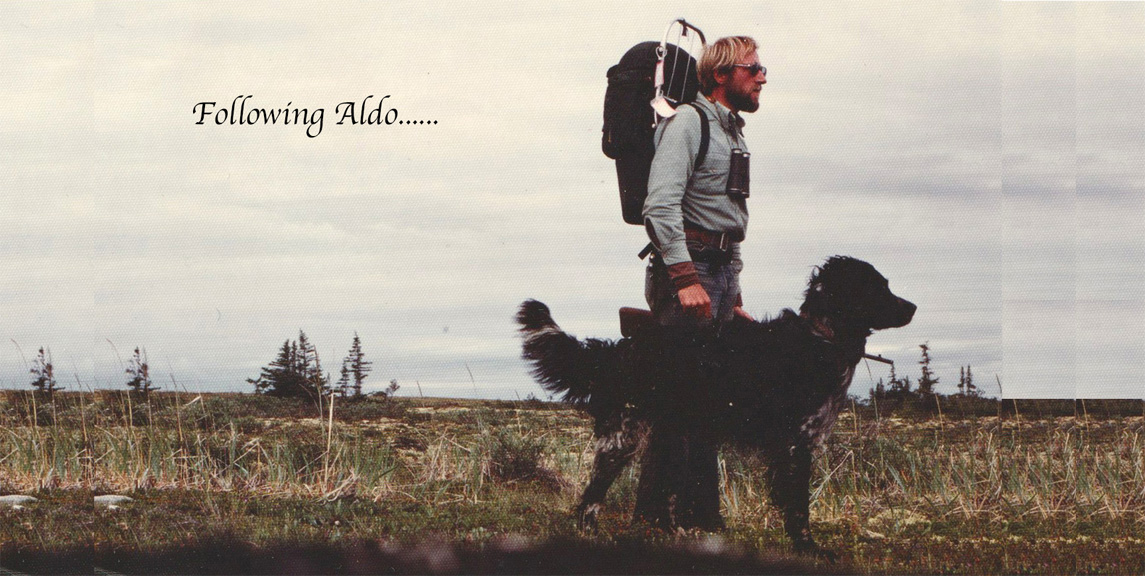

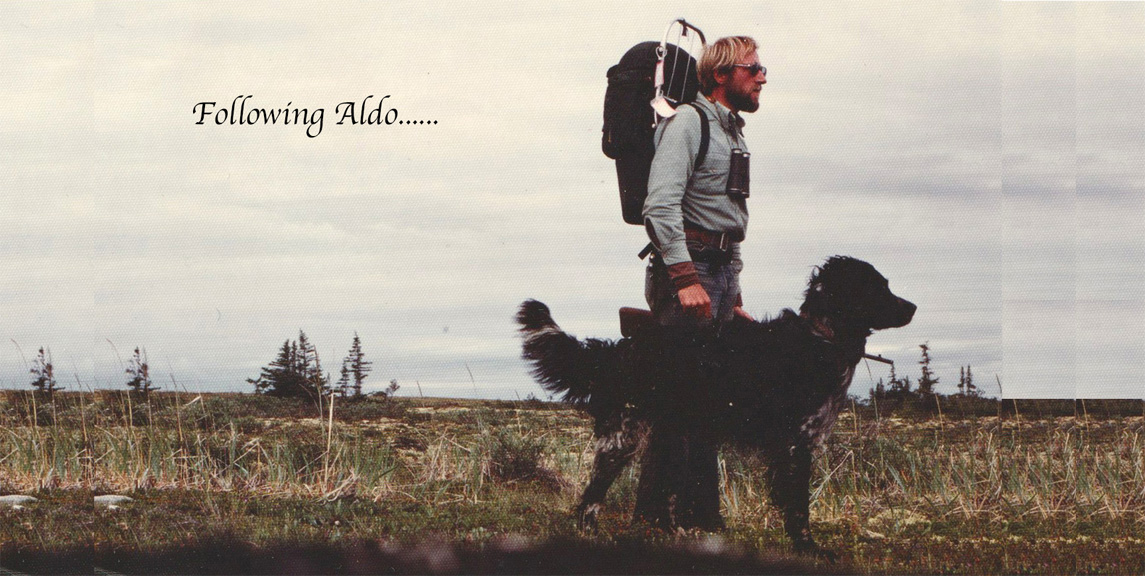

This somewhat fuzzy picture reminds me to try and bring clarity to life. It was a self-portrait with time-set camera on a rock. My dog Dachs and I walked from the Queen’s University’s La Pérouse Bay research camp, 25 km across the Coastal Hudson Bay Lowland. My field work on Common Eider ducks with Dachs’ help was done this late July 1979. The eiders with broods were moving out from the river delta to the Bay’s shores. Our destination was the National Research Council of Canada’s Rocket Research Station, the nearest road. From there I could call the Churchill Northern Studies Centre for a ride. The gun, ostensibly, was for protection from Polar Bears – luckily I did not have to use it. I saw one bear at a distance heading our way. Dachs and I hoofed it faster so the bear would scent our path well behind us.

- Schmutz, J. K. (1979). "The versatile hunting dog in wildlife research." Hunting Dog 14(7): 44-45.

- Schmutz, J. K., Raleigh J. Robertson and Fred Cooke (1982). "Female sociality in the common eider duck during brood rearing." Canadian Journal of Zoology 60(12): 3326-3331.

- Schmutz, J. K., Raleigh J. Robertson and Fred Cooke (1983). "Colonial nesting of the Hudson Bay eider duck." Canadian Journal of Zoology 61(11): 2424-2433.

- Schmutz, S. M., J. K. Schmutz, N. E. Simpson, and H. Tabel (1987). "Serum protein polymorphism in common eiders detected by isoelectric focusing." Biochemical Genetics 25: 191-195.

|

|

|

Fran and Frederick (Hammi) served as my sponsors while I attended the University of Wisconsin at Stevens Point 1970-74. I held a student visa while in the U.S., as a Landed Immigrant to Canada. Thanks to Fran, Sheila and a host of others, I, who graduated from a German trade school without High School, received a B.Sc. with Honours.

|

|

|

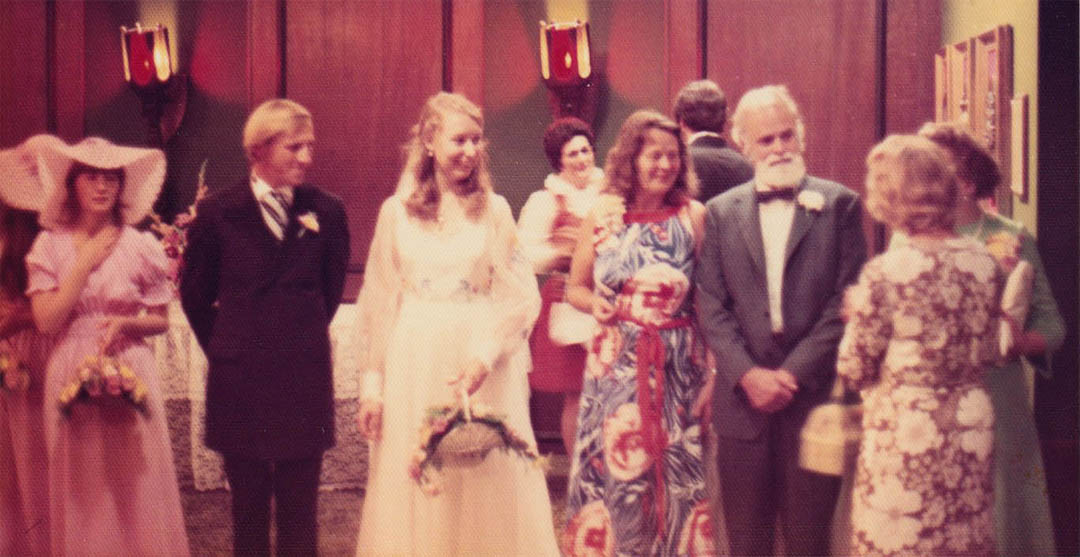

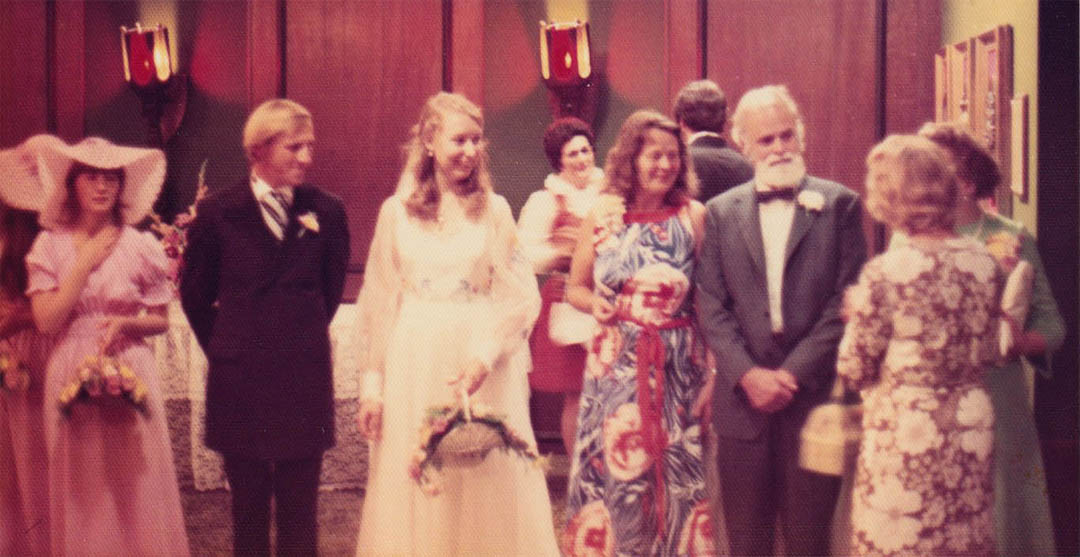

Sheila (née Stark) and I were married in August 1972.

|

|

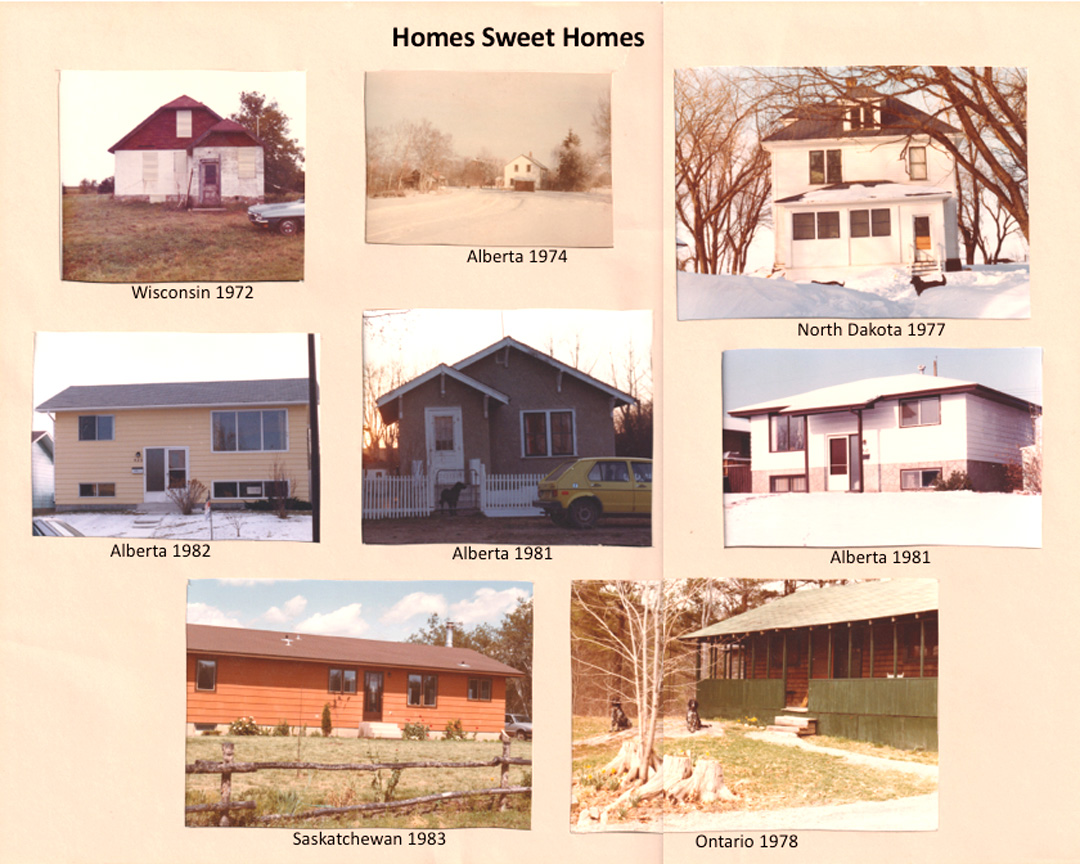

On Fran’s suggestion we moved into an abandoned farm house surrounded by their beloved Greater Prairie Chickens, on the Buena Vista Marsh.1 We brought the Large Munsterlander Amsel von Siegerland from Germany on our honeymoon. The Great Horned Owl, Tristan was going to be our falconry bird. Yet when we moved to Alberta, falconry was still illegal. Tristan moved to Fran and Hammi’s porch instead. Fran and Hammi were our mentors and idols.

|

|

We were their Northern-Harrier-study Gabboons in 1973.2 With Fran and Hammi’s data, and some we helped collect, we published our first manuscript. We can never thank Fran and Hammi enough for their generosity, not to mention the rich life experiences they prompted for us. On top of that, we can say we touched someone who’d touched Aldo.

- Schmutz, Josef K., and Sheila M. Schmutz (1975). "Primary molt in Circus cyaneus in relation to nest brood events." Auk 92: 105-110.

- Schmutz, Sheila M., and Josef K. Schmutz (1975). "Rearing and release of two young American Kestrels (Falco sparverius)." Journal of Raptor Research 9: 58-59.

1 Hamerstrom, Frances, illustrated by Elva Hamerstrom Paulson (1980). "Strictly for the chickens." Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa, USA; 174 pp.

2 Hamerstrom, F., illustrated by Jonathan Wilde (1986). "Harrier, hawk of the marshes: The hawk that is ruled by a mouse." Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C., U.S.A.; 171 pages.

Fran and Hammi, and their mentor Aldo Leopold indirectly, opened so many doors to my life? Aldo Leopold was a towering figure in conservation, in what we call sustainability today and in nature-experience generally. Far be it from me to think I deserve to stand on the shoulder of this recent Great. Yet, I trust that he wouldn’t mind my using what I know about his life as inspiration for my own.

On this webpage, I share articles and projects that touch on my life as a biologist/scientist, teacher, conservationist and hunter – all of these relied on and strengthened a deep fascination for nature. Naturally, not all challenges are welcome challenges. Yet, overall, my life close to nature, has been joyful and rewarding.

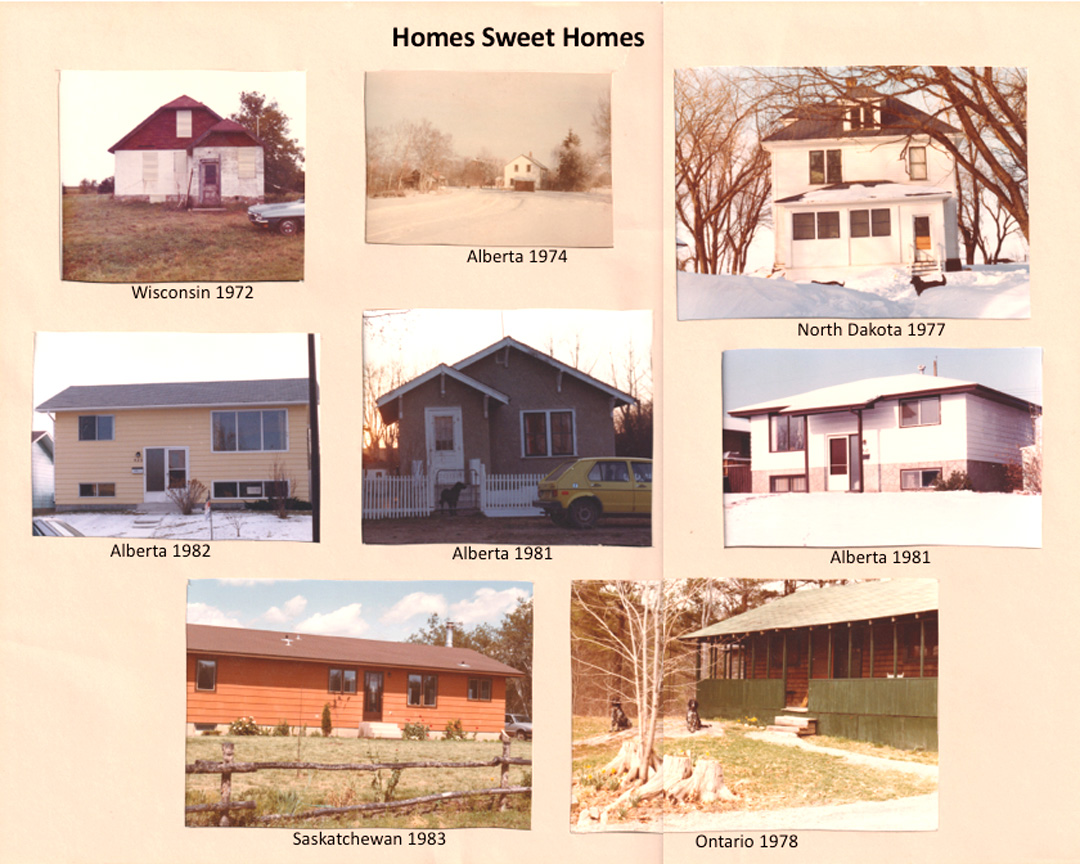

Between us, Sheila and I enjoyed much freedom, including a critically independent spirit at times. We were not slaves to student loans – Fran’s influence of making the best of abandoned farmhouses plus help from family saved us. We liked kids and supported our young relatives, but we were not bound to save up for their education. We balked when we felt that a push for conforming professionally got in the way of things. We reflect on our lives confidently, yet we are not ignorant of our failures along the way.

In Sand County Almanac (p. 127) Leopold wrote:

“When I call to mind my earliest impressions, I wonder whether the process ordinarily referred to as growing up is not actually a process of growing down; whether experience, so much touted among adults as the thing children lack, is not actually a progressive dilution of the essentials by the trivialities of living. This much at least is sure: my earliest impressions of wildlife and its pursuit retain a vivid sharpness of form, color, and atmosphere that half a century of professional wildlife experience has failed to obliterate or to improve upon.”

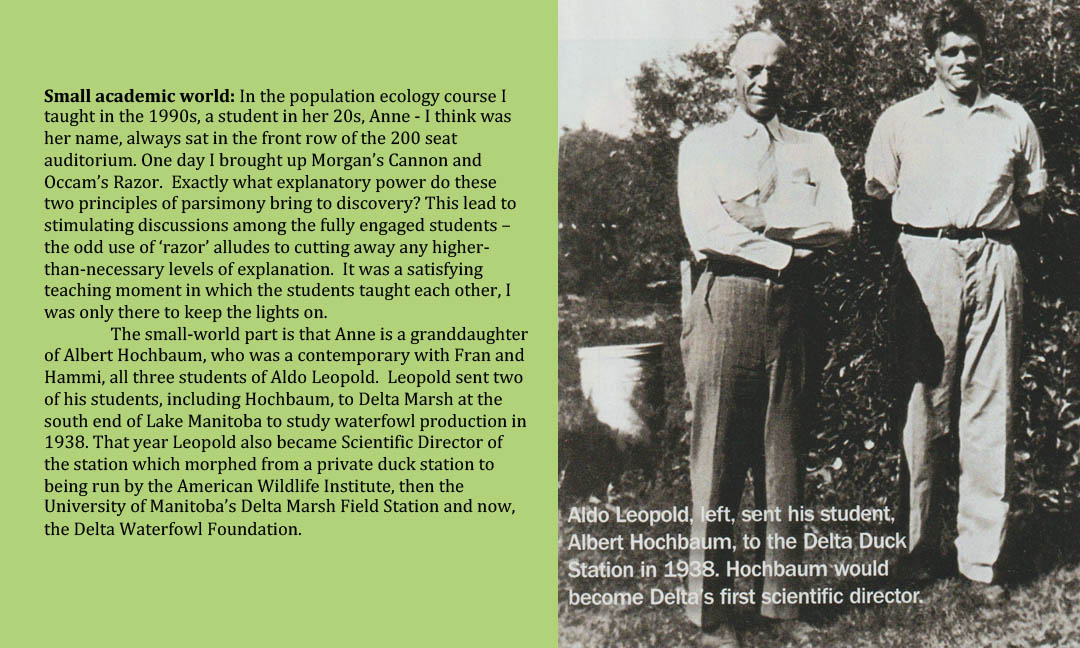

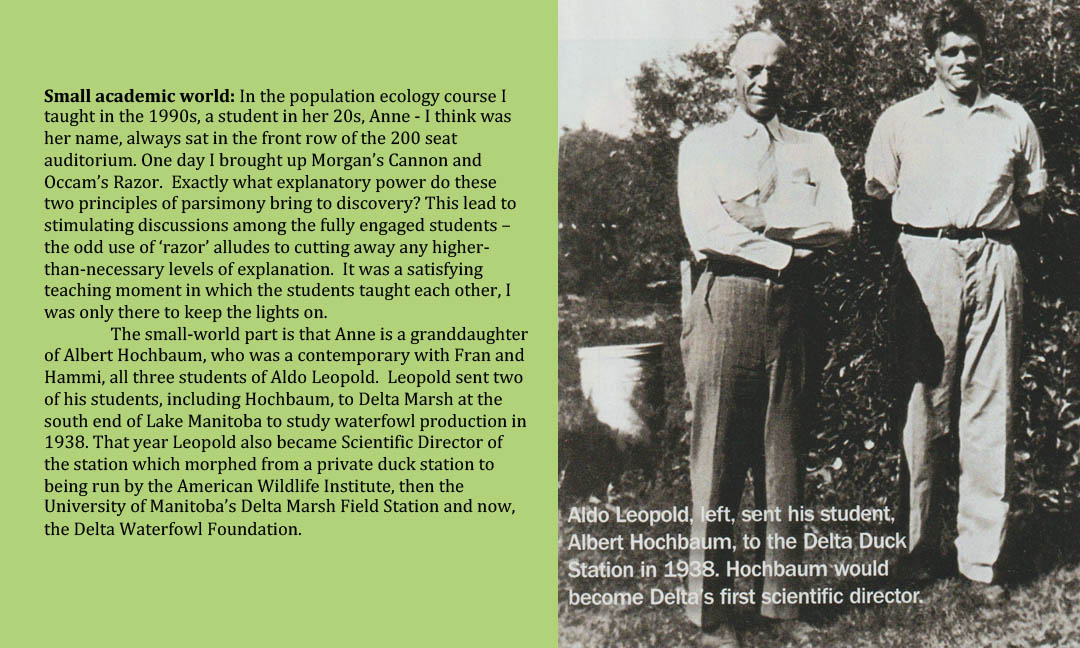

From: Wait, Paul (2024). "Aldo Leopold helped launch Delta Waterfowl’s science program." Delta Waterfowl Magazine (Winter 2024): 12-13.

Following 2025-2: The article below, Schmutz, J. (2025). "Wild in the cold." Blue Jay 83.1:19 was my attempt to capture how the pictured sharp-tailed grouse lived in its cold setting outside our window. Maybe this is what Leopold meant with his ‘pursuit of wildlife form, color, and atmosphere.’

|

Wild in the Cold This sharp-tailed grouse is showing one of at least three ways wildlife can deal with extreme cold. One way is staying out of the wind. For that they need favourable habitat. Another is staying put, moving little to keep the body’s heat windows covered and energy saved. Ungulates do that big time. Like cows, they have bacteria in their rumen busily creating warmth, boosting the animal’s own metabolic heat. In a third option, the pictured grouse is fluffing it’s feathers on a sunny afternoon at -22o C, after visiting our bird feeder. It’s body looks like a small soccer ball, nearly twice as wide as the bird’s bony frame. The feathers are tipped outward creating air spaces underneath them. Their curvature and elasticity allows overlap with the next feather, keeping insulating air spaces sealed up. At the tip of the feather is a half-circle of pigment. This adds strength to the feathers, as black or brown pigment does in a horse’s hoof. In the picture, there is not a single grouse feather out of place – that translates to survival value. Nature’s feather design combined with grouse behaviour maintain body temperature, which in birds is even higher than our own, at 41o C.

|

Where does our interest in ‘pursuing wildlife form, color, and atmosphere’ come from?

It calls to mind some of my own early impressions:

I might have been 10 at the time, when my dad and I drove from our traditional German mixed-farm in town to a satellite barn and apple orchard 1 km away. The hooves of Emma and Fritz, sounded like a metronome on the pavement. The horse-hoof metronome was soothing, maybe that calmness inspires so many people to live with and use horses.

At the intersection, the horses turned onto gravel into our orchard. I asked Papa, “How did the horses know that we wanted to turn here and not go to the big field further on?” He just shrugged, smiled and prepared for our arrival.

On another trip, the green Lanz Bulldog tractor pulled the wagon, not horses. We stopped at dozens of tripod frames that held hay for labour-intensive drying. In a landscape with 75 cm of rain annually, drying grass on the ground is risky.

Papa stopped and walked to a nearby drying frame. He reached inside to test the inner layers of hay for stem pliability and dryness, as I’d seen him do countless times before. Papa came back and handed me a molted raptor flight feather, likely from a Buteo buteo. I call it the Mäusebussard because I dislike the English common name Common Buzzard for both words’ connotations.

Raptors used those hay racks as a perch from which to rest, preen and hunt. Molted feathers can fall and lay on top. To my question “Why did that raptor put the molted feather inside the hay?” Papa gave me the same casual shrug as with the horses.

It was only much later that I put two and two together.

All the lead mare Emma needed was a subtle flip of the reigns leftward to have taken the turn into the orchard – a signal I missed but Emma did not. Similarly, I just missed seeing Papa’s reach to pick up the beautiful feather off the top.

There must be an education lesson buried in these events. Papa’s shrugs engendered searching, pondering and observing both horses and wildlife. That was likely a form of experiential learning, far more valuable than the closure of a final answer.

Were those experiences at the root of my passion for wild lands, wildlife and domestic animals, particularly hunting dogs. To this day and now in my 70s, I still feel that sense of wonder, even awe, when a raptor dashes past our big living room windows. Especially goshawks come by to try and nab a homing pigeon from the flock we invite to live here and use for training young pointing dogs. ... and to this day, I still wonder and ask why wildlife, landscapes and us do the things they do.

Following 2024-12: From that night in June 1970, when I drove into Fran and Hammi’s yard past midnight, to start university 2-days later, I’d been near Fran’s Golden Eagles on and off, Chrys and Brendel. They were awesome birds. There are bigger birds even, raptors, swans, geese and ostriches but none have the elegant form of Golden Eagles. It’s no wonder that so many nations, young and old, have eagles in their coat of arms – not ostriches. The beak alone - powerful with streamlined elegance. From beak, down the neck and over shoulders, all the parts seem efficiently aligned for an aerial-hybrid-land, rock and even watery existence.

|

Little did I know that years later I would learn much more about the Golden Eagle’s capable elegance. I was contacted by an acquaintance in the U.S., asking what data did I have about Golden Eagles in Canada? Not much I said – I’d maybe seen 30 golden eagle nests in comparison to many hundreds of prairie hawks throughout my 3-decades of studies. I contacted my now late friend Stuart Houston, who besides a productive career as a professor of radiology studied Golden Eagles in southern Saskatchewan for 43 years!

It took me 2 years and two editorial rejections, before the 33-page article saw the life in both print and internet as a special 75th Anniversary Issue of the Saskatchewan based journal the Blue Jay.

|

|

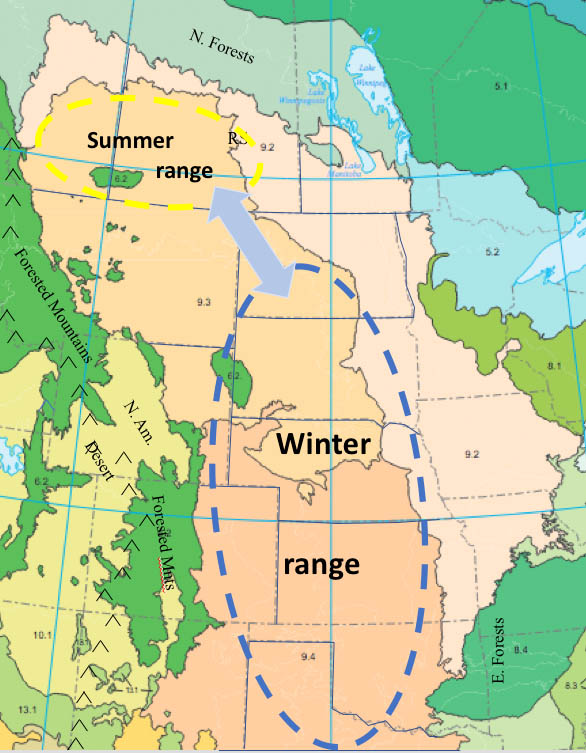

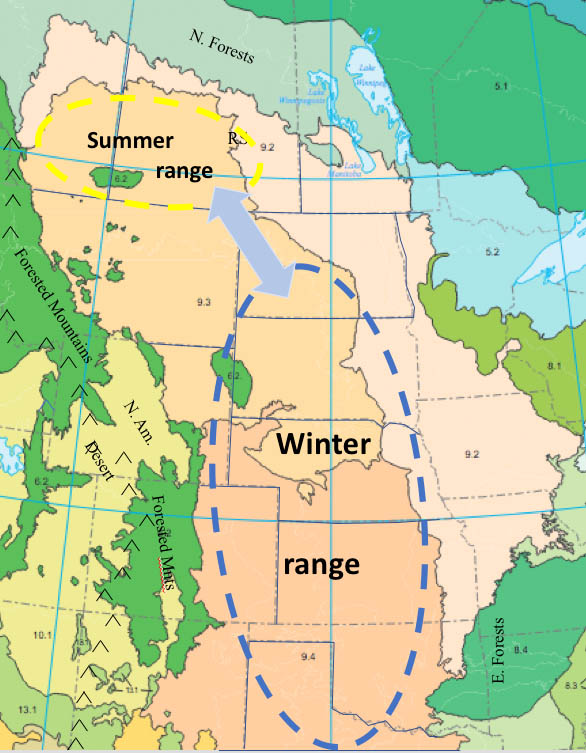

Even after their deaths, the article pays tribute to the work of the Canadian Wildlife Service research scientist Richard W. Fyfe and C. Stuart Houston. Of several meaningful conclusions reached, are the widespread declines of prairie jackrabbits – the eagle's main prey. We could also show that our prairie nesting Golden Eagles spend their entire breeding, migration and winter existence on the Great Plains, separate from northern Canadian eagles of the Rockies, those in the U.S. Great Basin and those in the Midwest and eastern Canada.

|

|

Following 2023-5 As noted above, I was to learn that Golden Eagles are capable and elegant. I was amazed and initially doubted my own research conclusion that Golden Eagles were not in trouble in Prairie Canada numbers wise. We’re taught that top level predators are at a greater risk of decline than animals nearer the bottom of the food pyramid – goes to show that big generalizations can only go so far.

At our northern Great Plains, plants, animals and even basic ecological processes are at risk, why not Golden Eagles? My considered conclusion is that the eagles’ struggled before Europeans settled and changed the prairies, and they may struggle again. Up to now, they’re lucky.

My conclusion is based on some long-term trends in the grasslands. Aldo Leopold used this kind of systems thinking in his Sand County Almanac1 “Thinking like a mountain” where predators, prey, plant communities and landscape operate together. Fran gives it away in her book title, “The hawk that is ruled by a mouse”. Wes Olson and Johanna Janelle 2 excelled at ecosystem analyses relative to Bison as much or more than most.

In a nutshell, when the rain-shadow, Bison and fire ruled the prairie, woody vegetation was scarce.3 Woody shrubs are the Jackrabbit’s main food and without jackrabbits eagles struggle. Today, woody vegetation is abundant.4 Jackrabbits have had their heyday and so do/did eagles. The widespread decline in Jackrabbits these days (2024-12) presents a question mark for the eagle’s future.

- 1 Leopold, Aldo. (1966). "A sand county almanac: With essays and conversations from Round River, and illustrations by Charles W. Schwartz." Ballantine Books, New York; 295 pp.

- 2Olson, Wes, and Johane Janelle (2022). "The ecological buffalo: On the trail of a keystone species." University of Regina Press, Regina, Saskatchewan, 280 pp.

- 3Spry, Irene M. (1963). "The Palliser Expedition: The dramatic story of Western Canadian Exploration 1857-1860." Fifth House Publishers, Calgary, Alberta: 315 pp.

- 4Houston, C. Stuart, and Josef K. Schmutz (1999). "Changes in bird populations on Canadian grasslands." Studies in Avian Biology No. 19:87-94.

|

Should you be interested in an audio presentation, here's the YouTube link

|

Following 2023-4 Aldo Leopold was clearly fond of his hunting dog.

"We sally forth, the dog and I, at random. He has paid scant respect to all these vocal goings-on, for to him the evidence of tenantry is not sound but scent. Any illiterate bundle of feathers, he says, can make a noise in a tree. Now he is going to translate for me the olfactory poems that who-knows-what silent creatures have written in the summer night. At the end of each sits the author—if we can find him. What we actually find is beyond predicting: a rabbit suddenly yearning to be elsewhere; a woodcock, fluttering disclaimer; a cock pheasant, indignant over wetting his feathers in the grass.

Fran and Hammi were deeply attuned to wildlife. They subscribed to Konrad Lorenz's conviction that living with wild animals and observing their very nature without interfering can teach us things. Yet with hunting dogs, Fran and Hammi struggled, as Helen Corneli noted in "Mice in the freezer, owls on the porch".

This may be, because Fran and Hammi expected dogs to work capably before and after the shot in the upland and water – after all, that's what hunting is. There was not yet a versatile-hunting-dog tradition in North America, not an expectation for one and the same dog to do all these tasks well. It required different breeds to do the separate hunting tasks: the trailers, the pointers and retrievers. The Allied Soldiers who saw the full-utility hunting dogs in action during the post-war European occupation had not yet been able to tell their stories. Continental "wonder dogs" they called them.

One day Amsel and I got to hunt with Fran and Hammi. We walked around 'The Pond' that every Gabboon knew and treasured. On the east side, a shot rang out. Hammi had dropped a woodcock out of sight into dense willows. As I walked toward him, Amsel found the woodcock without our help, and naturally brought it. Hammi was impressed, not every dog will pick up woodcock he said.

There are several hunting dog cultures that provide choices for hunters. For example, "A Tail of a Dog: There are different views on what a dog on point should look like."

Amsel (3rd from left) and I at an Ontario NAVHDA Utility Test in 1978. Amsel stands among versatile hunting dog breeds originating in France, Germany and Hungary.

I have two overlapping passions in my life:

|

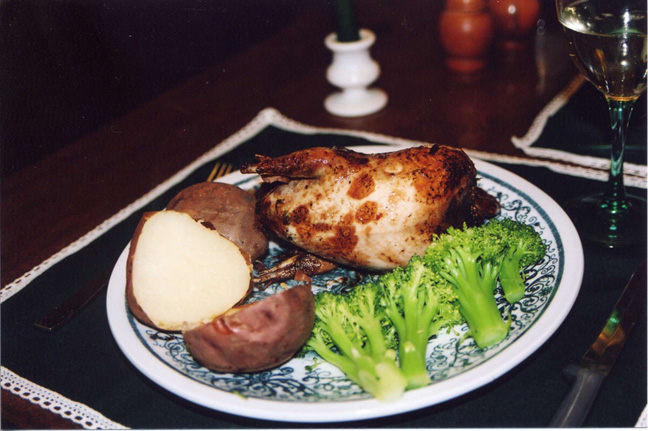

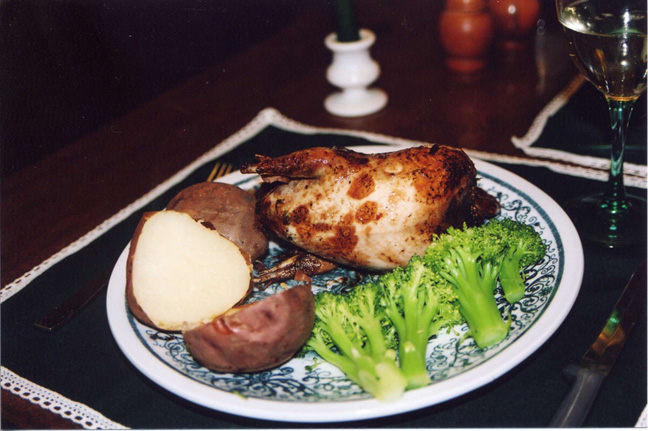

CONSUMPTION BIOLOGY

Joe is an avid bird hunter who uses Large Munsterlanders to aid in this pursuit. Joe and Sheila eat everything he hunts, with the dogs finishing off the bones.

|

|

Related Webpages

For further information, e-mail Joe Schmutz.